Maurice Fraser, my friend and woodworking mentor, passed away last Sunday night. He was 87. I first met Maurice in the mid-1980's when I took a summer class in woodworking at the Craft Students League of the YWCA in Midtown Manhattan. From there I spent three years taking Maurice's woodworking classes at various levels, eventually becoming one of Maurice's class assistants. Maurice taught evenings at the Craft Students League for over 30 years. Maurice Fraser, my friend and woodworking mentor, passed away last Sunday night. He was 87. I first met Maurice in the mid-1980's when I took a summer class in woodworking at the Craft Students League of the YWCA in Midtown Manhattan. From there I spent three years taking Maurice's woodworking classes at various levels, eventually becoming one of Maurice's class assistants. Maurice taught evenings at the Craft Students League for over 30 years.

While it is fair to say that different styles of teaching appeal to different types of students - and not every teacher is right for every student - in my case, the match was perfect. Maurice wasn't interested in teaching students how to build projects. He wanted students to learn basic techniques well so that they could build anything.

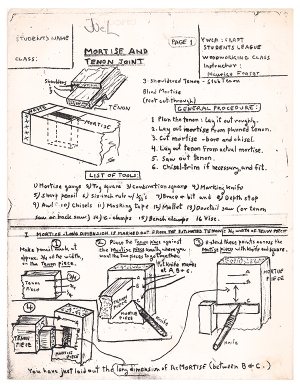

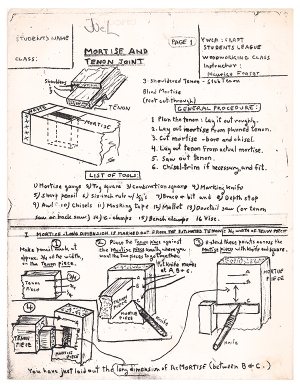

Each lesson was a careful dissection of a technique, sharpening, mortising, dovetailing, finishes, etc. Maurice taught using not just one method, but a comparison of advantages and disadvantages of many different approaches. Each class was accompanied by a distribution of "notes," a series of papers that illustrated the methodology being taught. Many students, including me, would routinely consult the notes for sequence and tips when we did the actual work. Like many of Maurice's students, I kept these notes all these years, long after evening classes ended. If you click on the picture below I have scanned and uploaded a set from his mortise-and-tenon lectures. The last page, which is very poorly reproduced, was typical of Maurice. Every year, before each topic was introduced he would routinely cross out, re-edit, and alter the notes. Trying each time to make them clearer and more focused. Many students - and there were a fair number from the publishing industry - urged him to write a book of his notes. But Maurice had trouble with that because he said, "They need to be cleaned up and some of the material could be a lot clearer." Sadly, this is a project he never completed.

Maurice's great skill was as a teacher. He understood how to experiment, dissect, then simplify and explain a subject so it made sense. For example, when the class studied hand planing, Maurice brought in a complete line of Stanley Bedrock planes and Norris planes from his personal collection so all the students could try them out for size. The goal was to understand which plane did what, and (within the family of bench planes, for example), which size fit your best. Maurice preferred a Bedrock 603. I ended up with a Bedrock 604.

Maurice did write articles for magazines, including Fine Woodworking, and contributed to a woodworking book by Reader's Digest. His sharpening lesson, which he taught first thing to every class of beginners, . As a traditionalist he used Arkansas stones for sharpening all his life, but very much believed that developing good technique for sharpening was more important than which stones you used. His lesson was turned into a short video which sadly is no longer in print.

Born in Philadelphia, Maurice served in the Army in post-war Japan; among his many jobs was guarding Prime Minister Tojo in prison. After the war Maurice became a bookkeeper in New York and hated every second of it. In desperation he quit his job and took a long trip to Germany. It was there his great love of music went from a dream to an active passion. Back in New York he worked as a harpsichord tuner and a taxi driver to make ends meet. In the 1960's Maurice decided to learn how to make musical instruments and took classes under Jere Osgood at the Craft Students League. When Jere Osgood left the position Maurice took over as the instructor.

Maurice's real passions in life were music and Connie, his wife of 60 years. Maurice moved into a boarding house in NYC in 1954 and met a roommate's gorgeous sister: Connie. They fell immediately in love and moved into a small apartment in the then rough-and-tough Upper West Side. They were together as a passionately devoted couple until Connie's death in 2013. Maurice stayed in that same apartment for the remainder of his life, surrounded by Connie's paintings and things that were beautiful of their own or made significant by the life Maurice and Connie lived together. Connie actually enrolled in his class a couple of times, unmasked as not just another attentive student by the the endearments Maurice couldn't help but use with her.

I learned a lot more from Maurice than things about woodworking. As I write this I am listening to the Lamentations of Jeremiah by Thomas Tallis. Maurice introduced me to William Byrd, Percell, and others. He never did get me to enjoy Bach, which was truly his favorite. Of course in typical Maurice fashion, after hearing that I liked Byrd, Maurice suggested that Byrd was "nice," but really I should be listening to Tallis (one of Byrd's teachers). He was right. Those who were fortunate enough to be invited to dinner with Connie and Maurice will never forget the experience: the most astounding feasts - technically complex, unless they were disarmingly simple, like a water-based garlic soup flavored with mace - and a succession of rapidly emptied bottles of really good wine. All from a tiny (even by NYC apartment standards), very dimly lit kitchen. Connie's passion was traditional cooking. If you were there on Christmas (and I was), you got a goose dinner that Tiny Tim and Scrooge would recognize. Connie was the single finest home cook I ever had the fortune to sit at table with, but was also a wonderful, encouraging and appreciative guest at someone else's table. Maurice, with his typical attention to detail, introduced me to fine wine and fine dining.

Maurice's passing marks the end of an era for me, and for so many of his former students in the Maurice diaspora.

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

Maurice Fraser, my friend and woodworking mentor, passed away last Sunday night. He was 87. I first met Maurice in the mid-1980's when I took a summer class in woodworking at the

Maurice Fraser, my friend and woodworking mentor, passed away last Sunday night. He was 87. I first met Maurice in the mid-1980's when I took a summer class in woodworking at the

Perhaps in their passing we come to realize that the things we learned from them can only be memorialized by handing the lessons down to the next generation of students.

We all stand upon the shoulders of giants.

Regards, Wes

Our love ones may be physically gone but their memories last forever.

P.

Wayne

What a lovely tribute to your friend, May he rest in peace. Great teachers are hard to come by, and even harder to find a great friend. May you be that inspiration for an up and coming young woodworker!